210 Episodes · 73h13min

- Solving the View Model Problem (Part 2) 14:59

- Solving the View Model Problem (Part 1) 18:59

- Settings Form Layout (Part 2) 16:40

- Settings Form Layout (Part 1) 16:54

- ThumbHash (Part 6) 16:54

- ThumbHash (Part 5) 19:12

- ThumbHash (Part 4) 31:06

- ThumbHash (Part 3) 21:19

- ThumbHash (Part 2) 22:26

- ThumbHash (Part 1) 22:26

- Visual Node Editor (Part 9) 22:29

- Visual Node Editor (Part 8) 18:51

- Visual Node Editor (Part 7) 24:59

- Visual Node Editor (Part 6) 15:57

- Visual Node Editor (Part 5) 17:09

- Visual Node Editor (Part 4) 31:52

- Visual Node Editor (Part 3) 20:01

- Visual Node Editor (Part 2) 15:39

- Visual Node Editor (Part 1) 27:10

- SwiftUI as Static Site Generator (Part 6) 32:13

- SwiftUI as Static Site Generator (Part 5) 21:21

- SwiftUI as Static Site Generator (Part 4) 28:18

- SwiftUI as Static Site Generator (Part 3) 20:58

- SwiftUI as Static Site Generator (Part 2) 20:38

- SwiftUI as Static Site Generator (Part 1) 22:16

- Building a Token Field (Part 5) 27:40

- Building a Token Field (Part 4) 16:06

- Building a Token Field (Part 3) 19:05

- Building a Token Field (Part 2) 25:12

- Building a Token Field (Part 1) 23:10

- Building a FaceTime-like Animation (Part 2) 18:48

- Building a FaceTime-like Animation (Part 1) 16:08

- Staggered Animations Revisited (Part 3) 14:03

- Staggered Animations Revisited (Part 2) 16:31

- Staggered Animations Revisited 00:00

- Custom Format Styles 20:31

- Text Formatting 21:13

- Keeping Local View State in Sync 19:35

- Optional Bindings 27:15

- Attribute Graph (Part 10) 17:10

- Attribute Graph (Part 9) 32:16

- Attribute Graph (Part 8) 20:57

- Attribute Graph (Part 7) 23:53

- Attribute Graph (Part 6) 25:44

- Attribute Graph (Part 5) 28:20

- Attribute Graph (Part 4) 26:32

- Attribute Graph (Part 3) 20:10

- Attribute Graph (Part 2) 22:12

- Attribute Graph (Part 1) 20:35

- Particle Effects (Part 6) 15:02

- Particle Effects (Part 5) 12:37

- Particle Effects (Part 4) 21:04

- Particle Effects (Part 3) 18:16

- Particle Effects (Part 2) 16:25

- Particle Effects (Part 1) 14:28

- Lazy Container Views (Part 4) 28:54

- Lazy Container Views (Part 3) 20:16

- Lazy Container Views (Part 2) 18:50

- Lazy Container Views (Part 1) 16:05

- Bento Layout (Part 4) 10:06

- Bento Layout (Part 3) 27:25

- Bento Layout (Part 2) 13:33

- Bento Layout (Part 1) 13:16

- Environment & Preference Updates 15:30

- Tooltips (Part 2) 00:00

- Tooltips (Part 1) 17:14

- Detecting Visible Cells 17:57

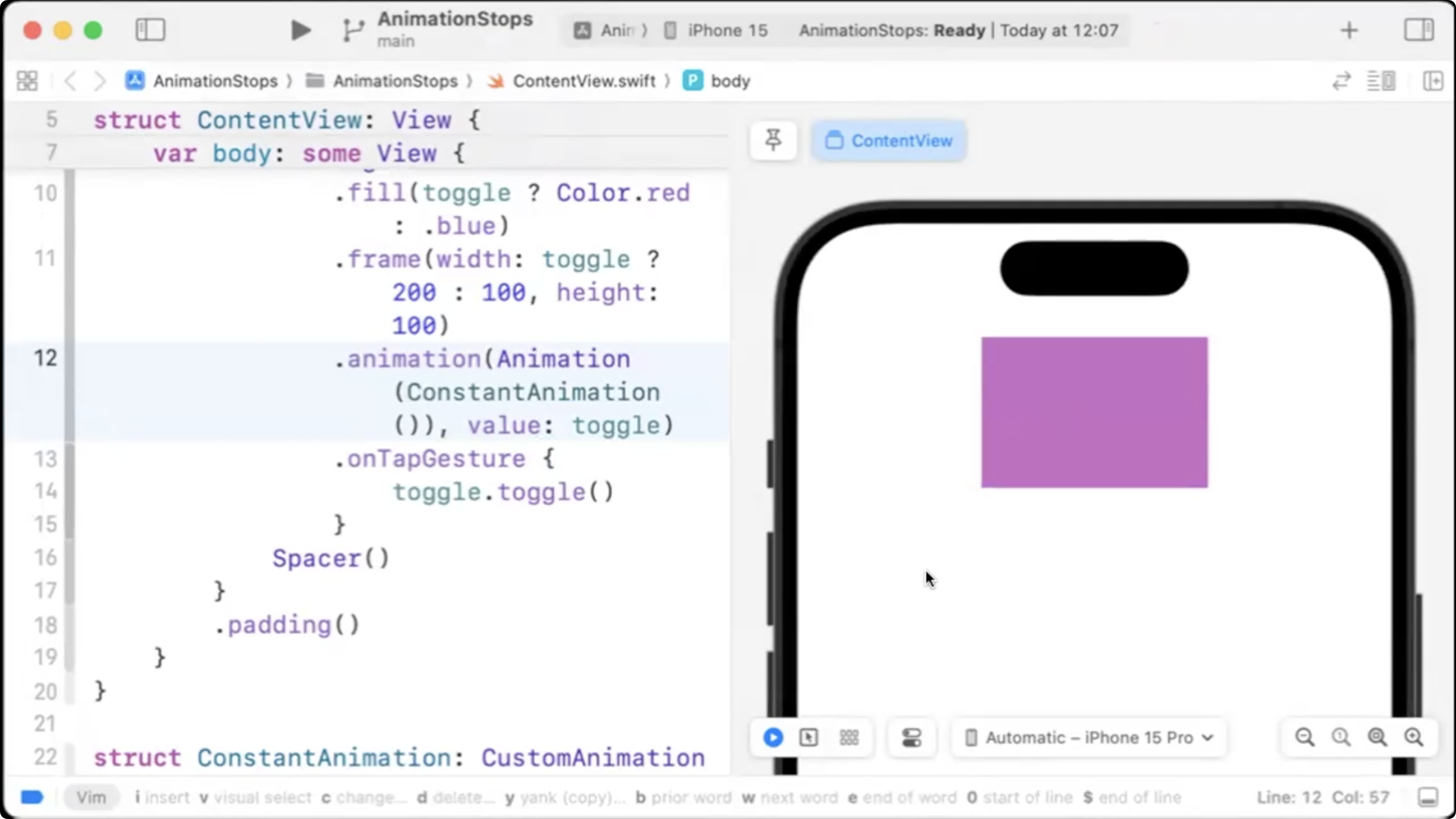

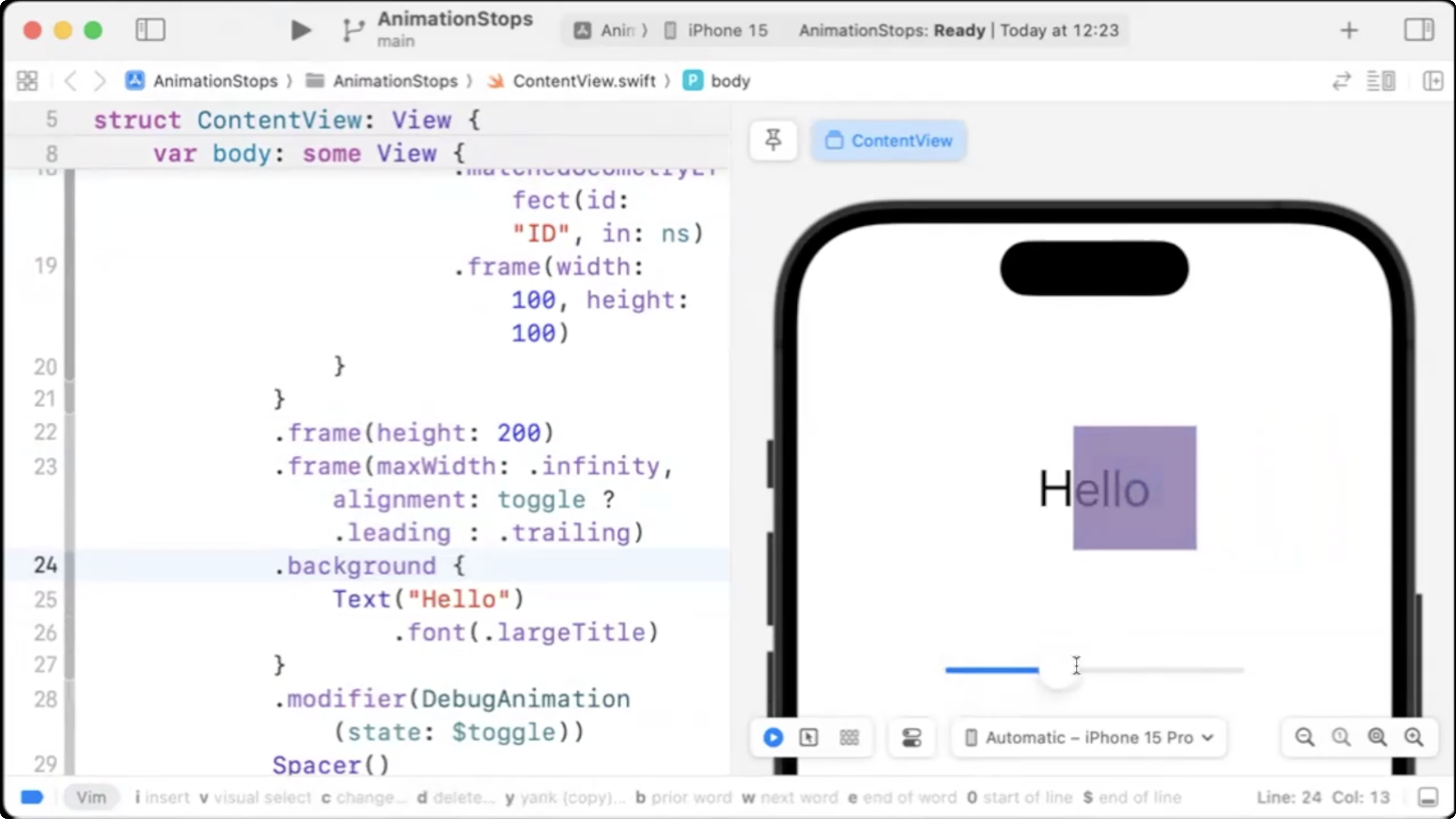

- Debugging Animations 23:16

- Picker Animation (Part 2) 13:59

- Picker Animation (Part 1) 17:06

- Wobble Animation 21:08

- Positioning Badges (Part 2) 17:56

- Positioning Badges (Part 1) 14:10

- Reimplementing the Default Button Style 18:17

- Conditional Aspect Ratio Modifier (Part 2) 17:45

- Conditional Aspect Ratio Modifier (Part 1) 21:20

- Building a Legend View (Part 3) 18:22

- Building a Legend View (Part 2) 28:56

- Building a Legend View (Part 1) 23:34

- Pattern Shape Styles 25:03

- Tweakable Values: Finishing Up 22:35

- Tweakable Values: Custom Editors 16:24

- Tweakable Values: Generics 28:35

- Tweakable Values: Basic Approach 24:13

- Interactive Marquee View (Part 4) 14:25

- Interactive Marquee View (Part 3) 22:54

- Interactive Marquee View (Part 2) 23:17

- Interactive Marquee View (Part 1) 23:08

- Cubic Bezier Keyframes (Part 5) 22:54

- Cubic Bezier Keyframes (Part 4) 19:55

- Cubic Bezier Keyframes (Part 3) 25:17

- Cubic Bézier Keyframes (Part 2) 19:40

- Cubic Bézier Keyframes (Part 1) 22:38

- Building Keyframe Animations (Part 3) 24:36

- Building Keyframe Animations (Part 2) 20:02

- Building Keyframe Animations (Part 1) 23:53

- Swift, the Language: Swift Observation: Observable Macro (Part 2) 11:38

- Swift, the Language: Swift Observation: Observable Macro (Part 1) 27:11

- Swift, the Language: Swift Observation: Calling Observers 17:43

- Swift, the Language: Swift Observation: Access Tracking 22:08

- Connecting Lines with Anchors (Part 3) 24:46

- Connecting Lines with Anchors (Part 2) 20:15

- Connecting Lines with Anchors (Part 1) 16:38

- Reimplementing Anchors: Transforms 21:09

- Reimplementing Anchors: Points 21:09

- Reimplementing Anchors: Bounds 27:47

- Flow Layout Alignment 24:06

- Swift, the Language: Attributed String Builder (Part 6) 17:59

- Swift, the Language: Attributed String Builder (Part 5) 20:41

- Swift, the Language: Attributed String Builder (Part 4) 23:18

- Swift, the Language: Attributed String Builder (Part 3) 16:30

- Swift, the Language: Attributed String Builder (Part 2) 19:30

- Swift, the Language: Attributed String Builder (Part 1) 16:32

- Scroll View with Tabs (Part 2) 24:38

- Scroll View with Tabs 20:24

- Sticky Headers for Scroll Views (Part 2) 20:59

- Sticky Headers for Scroll Views 25:37

- Staggered Animations with Animatable Views 17:42

- Staggered Animations with Variadic Views 17:42

- Staggered Animations 21:54

- Async Image: Cleaning Up 19:36

- Async Image: Caching 14:53

- Async Image: StateObject vs ObservedObject 24:19

- iPhone Simulator Chrome (Part 2) 23:09

- iPhone Simulator Chrome (Part 1) 21:34

- Custom Components: Creating a Custom Stepper 21:11

- Custom Components: Creating a Custom Stepper 29:00

- Custom Components: Making the Stepper Styleable 16:27

- Custom Components: Creating a Custom Stepper 18:02

- Custom Components: Introduction 20:57

- Inspecting HStack Layout 22:48

- Inspecting SwiftUI's Layout Process 18:09

- Search for a Mac App: Jumping to Search Results 24:02

- Search for a Mac App: Generating Search Results 18:56

- Search for a Mac App: Search Field & Completions 19:51

- Building a Photo Grid: Refactoring 23:31

- Building a Photo Grid: Gestures 14:42

- Building a Photo Grid: Spring Animation (Part 1) 29:35

- Building a Photo Grid: Gestures 17:41

- Building a Photo Grid: Animations 20:15

- Building a Photo Grid: Square Grid Cells 20:53

- The Layout Protocol 18:23

- Visualizing Async Algorithms: UI for Combining Algorithms 24:39

- Visualizing Async Algorithms: Combining Algorithms 23:38

- Visualizing Async Algorithms: Supporting More Algorithms 13:46

- Visualizing Async Algorithms: Interactive Inputs 26:28

- Visualizing Async Algorithms: Merging Async Streams 18:05

- Visualizing Async Algorithms: Timeline View 18:05

- Advanced Alignment (Part 3) 20:21

- Advanced Alignment (Part 2) 17:15

- Advanced Alignment (Part 1) 19:16

- Animations and Transactions 17:19

- Large Scrolling Graph (Part 3) 22:29

- Large Scrolling Graph (Part 2) 16:31

- Large Scrolling Graph 21:10

- Matched Geometry Effect (Part 3) 17:12

- Matched Geometry Effect (Part 2) 17:28

- AsyncImage 12:13

- Matched Geometry Effect (Part 1) 23:47

- Gestures and Animations (Part 2) 23:47

- Gestures and Animations 29:42

- Building a MapViewReader 17:46

- Flow Layout Revisited 25:53

- SwiftUI Layout Challenge 3 24:07

- SwiftUI Layout Challenge 2 18:00

- SwiftUI Layout Challenge 1 19:51

- Testing Animations with Previews 25:46

- Designing with Previews 19:34

- SwiftUI Slides: Footers 19:20

- SwiftUI Slides: Customizing Animations 16:54

- SwiftUI Slides: Styling Elements with View Modifiers 15:23

- SwiftUI Slides: Sizing Slides to Fit 18:47

- SwiftUI Slides: Function Builders 18:33

- SwiftUI Slides: Build Steps 26:25

- From MVC to SwiftUI — From Classes to Structs 22:24

- From MVC to SwiftUI — Refactoring Model APIs (Part 2) 21:22

- From MVC to SwiftUI — Refactoring Model APIs 29:01

- From MVC to SwiftUI — Lazy Observable Objects 22:56

- From MVC to SwiftUI — Wrapping UIKit Alerts 26:45

- From MVC to SwiftUI — Reusing the Model (Part 2) 32:35

- From MVC to SwiftUI — Reusing the Model 27:22

- Wrapping Map View 14:41

- SwiftUI Stopwatch App: Scaling Text to Fit 18:50

- SwiftUI Stopwatch App: Analog Clock (Part 2) 23:48

- SwiftUI Stopwatch App: Analog Clock 22:24

- SwiftUI Stopwatch App: Lap Times 21:50

- SwiftUI Stopwatch App: Adding the Data Model 27:27

- SwiftUI Stopwatch App: Self-Sizing Buttons 25:24

- SwiftUI Stopwatch App: Custom Button Styles 14:28

- Building a Shopping Cart: Cleanup & Refactoring 23:09

- Building a Shopping Cart: Drag & Drop (Part 2) 26:08

- Building a Shopping Cart: Drag & Drop (Part 1) 26:14

- Building a Shopping Cart: Transitions with View Modifiers 20:59

- Building a Shopping Cart Animation 26:33

- Animation Curves 23:58

- Building a Shake Animation 27:45

- Reordering with Drag Gestures 29:45

- Building a Collection View (Part 2) 25:32

- Building a Collection View (Part 1) 19:21

- Geometry Effects 25:02

- Animating along Paths 21:18

- Paths and Shapes 16:51

- Login and User Sessions 20:17

- Two-Way Bindings 18:35

- Integrating UIKit Components 31:31

- Lazy Data Loading 17:11

- Passing Data Around 24:16

- The Swift Talk App: First Steps 23:00

- Asynchronous Networking with SwiftUI 15:18

- A First Look at SwiftUI 17:32